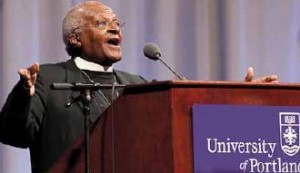

Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu brings message of ‘transformation through forgiveness’ to thousands in Oregon

Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu brings message of ‘transformation through forgiveness’ to thousands in Oregon

By Deirdre Steinberg

Oregon Episcopal Church News

The world’s best-known Anglican brought his message of “The Transformative Power of Reconciliation in Society,” to Oregon on May 4, when he was the honored speaker at Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon’s 40th Annual Collins Lecture. Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke to a sold-out crowd of 4,500 at the University of Portland for about one hour and then answered questions from a panel, which included one diocesan member, Charlene McGee, a parishioner of Grace Memorial, Portland, and a native of Liberia.

The Rev. Alcena Boozer, rector of St. Philip the Deacon, Portland, and past president of EMO, introduced Archbishop Tutu. Boozer called the archbishop’s appearance “an amazing event for all of us” and added: “Let us give thanks to God for bringing us all together from so many different faith traditions to experience the wisdom of this great man” and concluded her opening introduction with: “Let us pray that the power of love will someday overcome the love of power.”

The Diocese of Oregon was recognized as a “Gold Sponsor” of the event. The diocese’s sponsorship will help Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon look at ways the process of reconciliation and forgiveness can be applied to local communities here in Oregon, said David Leslie, EMO executive director.

Tutu, who was Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa, from 1986-1996, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. South African President Nelson Mandela appointed Archbishop Tutu chairman of the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1995, which investigated violence and human rights violations during the period of 1960-1994, when the country was in a civil war over the apartheid system of government. No part of South African society was unaffected by violence and abuse during the struggle against apartheid. The TRC was established to investigate the violations that took place, to provide support and reparation to victims and their families, and to compile a full and objective record of the effects of apartheid on South African society. In a monumental recasting of paradigm, perpetrators of any politically-motivated acts—including violations or abuse—could apply for amnesty from the TRC in return for providing a full account of their actions.

Saying ‘I am sorry’

Tutu told the audience. “The cynics said that a blackled government would strike back at whites in revenge for all the abuse that occurred under apartheid,” he recalle. “But as you know that didn’t happen. I believe we are made for goodness—all of us,” Tutu concluded.

The archbishop was not speaking in a Pollyannaish or naïve way about forgiveness and its redemptive powers, but from his own experience seeing many cases come before the TRC that turned out to deliver change for the good.

The ultimate forgiveness

One of the most powerful examples of the transformative power of truth and reconciliation was Tutu’s recounting of the death of Amy Biehl, a Stanford University student on a Fulbright Scholarship in Cape Town during the struggle against apartheid. Ironically, she was stabbed to death by four young anti-apartheid fighters, who saw only the color of her skin.

In 1998, Biehl’s killers were pardoned by the TRC (a decision her family endorsed) and released from prison after serving only four years. At the amnesty hearings, Amy’s parents actually shook hands with their daughter’s killers and her father, Peter Biehl, addressed the Commission amnesty hearings saying, “The most important vehicle of reconciliation is open and honest dialogue… we are here to reconcile a human life which was taken without an opportunity for dialogue. When we are finished with this process we must move forward with linked arms.”

Tutu called the Biehls’ reaction “mind blowing.” Two of Amy Biehl’s killers were employed by her parents at a foundation they established in Amy’s name that continues to this day to work to eradicate poverty in the slums of Cape Town. “Mahatma Gandhi was right,” said the archbishop, “where the maxim ‘an eye for an eye’ is employed, soon everyone will be blind.”

A model for the world

In 1995, just as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established, Archbishop Tutu wrote: “True reconciliation is never cheap. It is based on forgiveness, which is costly. Forgiveness in turn depends on repentance, which has to be based on an acknowledgement of what was done wrong and therefore on disclosure of the truth. You cannot forgive what you do not know.”

Truth Commission needed in US

Tutu told the audience that truth and reconciliation commissions similar to the model used in South African have been established in places such as Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Then, subtly and gently, the archbishop suggested: “And maybe one should be established here [in the U.S.],” which received a loud round of applause from the audience.

“I think the world is hungry for forgiveness and reconciliation,” said Tutu. The archbishop then talked about significant advances in relationships between warring factions in Rwanda, Northern Ireland, Kosovo, and Sri Lanka. He talked about the need in the Middle East for Jews and Arabs to take part in reconciliation and forgiveness while feeling secure and safe from each other’s attacks.

Finally, the archbishop told the audience that the need for a truth and reconciliation movement in the United States would benefit people of all colors, not just those of color. And, to thunderous applause, he gleefully said that “you have made a wonderful start just this year: Just look at your White House. “In terms of truth and reconciliation, ‘Yes, you can!’” Tutu concluded, echoing President Barack Obama’s famous campaign slogan.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.