Abstinence-Only Classes Reduced Sexual Activity, Study Found

Abstinence-Only Classes Reduced Sexual Activity, Study Found

Adolescents who took abstinence-only sex education classes were more likely to delay having sex, a new study shows. In the study, some 662 black 6th- and 7th-grade students, ranging in age from 10 to 15 with an average age of 12, participated in classes held on Saturdays at four Philadelphia public schools that draw from primarily lower-income neighborhoods.

Students either took eight hours of abstinence-only classes; eight hours of safe sex-only classes that included information about sexually transmitted diseases and the importance of using condoms if sexually active; or an eight- or 12-hour comprehensive course that covered both abstinence and safer sex.

Another group of students were enrolled in eight hours of a general health class that did not discuss matters related to sexual behavior. That group served as a control for comparison.

Two years after the courses began, with 84.4 percent of the students still enrolled in the program, students in the abstinence-only class were 33 percent less likely to have had sexual intercourse than the controls.

About one-third of students in the abstinence-only class reported they’d ever had sexual intercourse, compared with nearly half of the control group, the study authors noted.

Students who took the abstinence-only classes were also less likely to report having had sex recently, the researchers found. Of those who’d reported ever having had sex, about 21 percent of those in the abstinence group reported having sexual intercourse during the past three months compared to 29 percent in the control group.

The other intervention groups did not show statistically significant differences from the control group, according to the study.

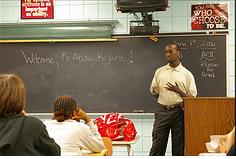

“This study shows an abstinence-only intervention can delay sexual intercourse among young, inner-city African-American adolescents,” said study author John B. Jemmott III, a professor of communication in psychiatry and of communication at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine and Annenberg School for Communication. “This is a population at very high risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, and unintended pregnancy.”

The study is published in the February issue of the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine.

The researchers said they could not be certain if a similar abstinence-only message would work among older teens.

The authors also stressed their study should not be read as an endorsement of all abstinence-only education. While facilitators encouraged delaying sex until some point in the future, they did not take a moralistic tone, portray sex negatively, use stereotypical depictions of men and women, or specifically tell students to wait until marriage, Jemmott said.

Nor did facilitators call into question the effectiveness of condoms, a common complaint lodged against some abstinence-only courses, Jemmott said. Facilitators in the abstinence-only classes were told not to bring up contraceptive use at all, unless a student broached the topic.

“If condoms came up, facilitators were taught they should correct any misconceptions and not allow arguments that disparage condoms to stand,” Jemmott said. “We knew this was an issue regarding abstinence-only education.”

In the abstinence classes, students role-played and did other small group activities designed to teach them that abstinence is the best way to eliminate the risk of pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, and to help the students develop the confidence to negotiate abstinence and resist pressure to have sex.

One of the fears about abstinence-only education is that teens would be less likely to use condoms once they started having sex. Researchers found no such connection in this study. Students in the abstinence group and students in the control group who went on to have sex were equally likely to have used condoms.

The study is sure to add fuel to the fire of sex education debates, a controversial topic for decades, said Bill Albert, chief program officer of the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

“This is really game-changing science,” Albert said. “For the first time, we have strong evidence that an abstinence-only intervention delayed sex and reduced recent sexual activity among young teens.”

The new information about what might work couldn’t come at a better time, Albert said: After more than a decade of decline, both the teen pregnancy rate and the teen birth rate have started rising again.

The U.S. teen pregnancy rate increased 3 percent in 2006, while the teen birth rate rose by 4 percent, according to a study released last week by the Guttmacher Institute.

Both the teen pregnancy rate and the birth rate had been falling since 1990 and 1991, respectively. Between 1990 and 2005, pregnancies among 15- to 19-year-olds dropped by 41 percent.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.