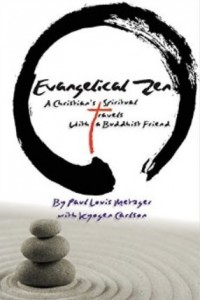

Book Review of Paul Louis Metzger, Evangelical Zen: A Christian’s Spiritual Travels With A Buddhist Friend

Book Review of Paul Louis Metzger, Evangelical Zen: A Christian’s Spiritual Travels With A Buddhist Friend

(Paul Louis Metzger is a Multnomah University professor)

Review by Derrick Peterson

Perfectly good words are all-too-easily haunted by histories they never intended. Hostages of ill-fortune, these once proud turns of the tongue find themselves the outcast amongst polite company. To give an example, in Christian history “gnostic” is one such word; used originally by many Church Fathers like Clement of Alexandria, it meant much the same that “disciple” does—a learner, one who knows because they have been taught by Christ, the Teacher. Usurped by the potpourri of mystical and theosophical beliefs we organize under the label “Gnosticism” for the sake of convenience, “gnostic” soon found itself no longer invited to Orthodox parties.

“Religious dialogue,” and “religious similarities” have as of late fallen victim to a similar process. At the far end of their history, both now smack of compromise, and not without reason. The idea that all religions teach the same thing once you look past the culturally relative forms which express them still looms large, of course. But more particularly there has been a history of scholars attempting to prove that Christianity was itself influenced by Buddhism. In his The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ, written in 1894 when “Lives of Jesus” literature was still en vogue, Nicolas Notovitch infamously argued Jesus had traveled to India before his Galilean ministry, and was influenced by Buddhism there. While Notovitch’s thesis was proven ill-conceived (not least after details surfaced that he had fabricated much of his evidence), the idea remains in the popular works of those like Elaine Pagels. As such, “Christian-Buddhist dialogue” or “similarities” between Christianity and Buddhism seems to many to be either a formula compromising the integrity of each, or an attempt to reduce one to the other.

To assume Paul Louis Metzger’s work Evangelical Zen, with responses from Abbot Kyogen Carlson of the Dharma Rain Zen Center, merely exemplify this compromise or reduction, would be a great mistake however. Zooming down from the lofty peaks of abstraction, this is a discussion based both in friendship, and in the lost art of going through (rather than around) one’s convictions. Being doctrinal without being doctrinaire, maintaining relationship and dialogue even amidst disagreement, are no small tasks, and this book is one of the strongest examples you can find.

Nor indeed are Metzger and Carlson’s exhortations to dialogue based on our “global humanity” a form of mushy liberalism. For Metzger, “global humanity” is an authentically Christian doctrine found in the notion of Imago Dei. Quoting the theologian and missiologist Leslie Newbigin, Metzger writes: “The Christian confession of Jesus as Lord does not involve any attempt to deny the reality of the work of God in the lives and thoughts and prayers of men and women outside the Christian church. On the contrary, it ought to involve an eager expectation of, a looking for, and a rejoicing in the evidence of that work.”

Yet, if such rejoicing in the unexpected presence of Christ should not be mistaken for a sort of melting-pot syncretism, it should not be mistaken either for seeking refuge in a safe and superficial happiness. These encounters, even—perhaps especially—among friends, are risky. St. Augustine in his Confessions once likened being saved in Christ as riding a board of driftwood, ragged among the waves; here in Evangelical Zen a sort of beautiful, oceanic melancholy haunts the prose of the text as both men serenely reflect on the great costs that purchased them their joy. The real question must be: when the waves come, what are you holding on to?

Such is not a simple thought experiment. This text came in the midst of the greatest cost: Abbot Kyogen passed away before final publication as his heart failed. It is testimony to the commitment and legacy of both that in Kyogen’s passing, the dialogue efforts did not cease. This was not a publicity stunt, nor an endeavor born merely of reluctant necessity. Paul Louis Metzger and Kyogen Carlson had been dialoguing since 2003, and since 2005 the Dharma Rain Zen Center and New Wine, New Wineskins, an academic institute out of Multnomah University in Portland, Oregon, have engaged in monthly potlucks and dialogues. I myself had the pleasure to meet Kyogen on several occasions. It is wonderful to see that through this work Kyogen’s memory lives on.

At the end of Herman Hesse’s famous novel, Siddhartha, a man named Govinda hears stories of an enlightened ferryman, and travels to meet him. Initially Govinda does not recognize that this ferryman is in fact his long lost childhood friend Siddhartha. It is not until Siddhartha requests Govinda kiss him on the forehead that the truths of the universe are unlocked to Govinda. In other words, a plausible way to read this ending is to say that truth is discovered only by the love bestowed within the foundations of friendship. This is not alien to Christianity. After his resurrection, the Gospel of John records that it is in the midst of a fire Christ prepared for them that the disciples first recognize he is in fact the Christ they thought they lost (John 21). In Luke, the disciples only recognize the resurrected Christ as he breaks bread with them (Luke 24:35). While there are many other themes at play (and, obviously, themes not wholly compatible between Christianity and Buddhism) one wonders if here we see the fact that it is now in friendship that the truth of Christ is most assuredly revealed.

If this is so, then Christ truly appears in this record of Metzger’s spiritual travels with his Buddhist friend. You can find no better example of humble, respectful, and doctrinally sound dialogue than this. One can only hope it inspires a future generation to act likewise.

Disclaimer: This book was provided free of charge by Patheos in exchange for an honest review.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.