By Eric Fruits, Ph.D.

Cascade Policy Institute

Vouchers and education savings accounts (ESAs) are a subset of school choice policies. Under these programs, families who withdraw their children from public district or charter schools receive a deposit of public funds into government-authorized accounts. Funds in those accounts can be used to cover private school tuition and fees, online learning programs, private tutoring, or homeschool materials.

Families participate in school choice programs for a variety of reasons: dissatisfaction with their assigned public schools, better opportunities for parental involvement, student safety, and teaching tailored to their students’ needs. Moreover, there is a general expectation that exercising school choice will improve students’ academic proficiency and provide greater educational attainment. It has been argued that competition for students among traditional public schools, charter schools, private schools, and homeschools guides schools to improve to retain their current students and to attract new students.

Proponents of school choice programs argue that vouchers and ESAs can improve student achievement, graduation rates, and college admission. Alternatively, opponents argue that school choice programs have no noticeable effect. Some opponents claim that voucher and ESA programs are associated with worse educational outcomes.

These claims are challenging to evaluate. In particular, each student is unique and comes from a unique set of family and social circumstances. As such, it’s impossible to evaluate a “but for” world in which a student pursued a different option from the actual chosen option. In addition, an examination of group-level statistics—by school, district, or state—provides only an average result and obscures what could be significant effects at the individual level. Transferring from a public to a private school might provide enormous benefits to some students, modest benefits to others, and make little difference to another group of students. Families don’t care about the average, they care about their unique student.

Another challenge to evaluating these claims is that the research often requires following students over time. Studies of high school graduation diplomas, college admission, and college graduation may require a decade or more of data from each student.

Even so, because academic achievement and educational attainment are key issues in the policy debate regarding vouchers and ESAs, it’s important to have an understanding of the empirical research and the conclusions that can be drawn.

Families investigating and participating in school choice programs likely differ from those who don’t participate—such as parents’ level of education as well as family income, family structure, and other socioeconomic factors. Fortunately, many studies examining school vouchers in the United States have used lottery-based programs as a “natural experiment” to control for these factors. For example, many voucher programs have caps on participation, meaning that the number of students who want to participate in the program exceeds the number of slots available. In these cases slots are assigned by lottery, so there should be little difference in demographic or socioeconomic factors among those who “won” the lottery compared with those who “lost.” Thus, a comparison of lottery “winners” and “losers” can be a reliable indicator of a program’s effectiveness.

Reviewing the known studies of voucher programs using such approaches, the research indicates:

- Voucher participants are more likely to have higher reading scores than those who don’t participate in the voucher program; math scores are more mixed;

- City-level studies are more likely to find positive effects of voucher programs than state-level studies; the difference between the results may be explained by the difference in tests used at the city level vis-à-vis the state level;

- Voucher participants are more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college.

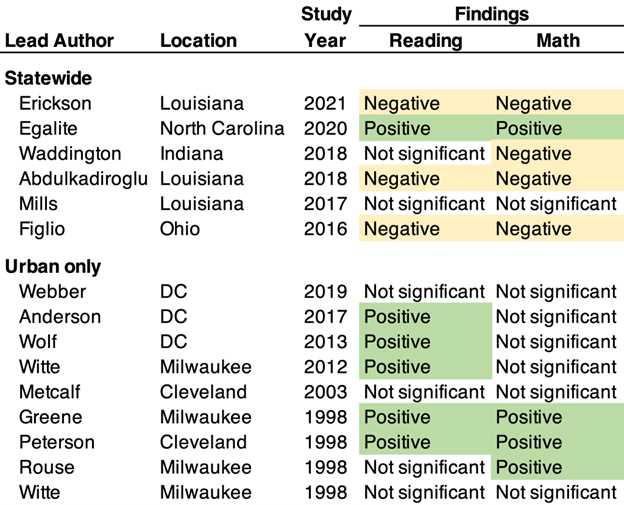

Reading and math scores

Empirical research provides mixed results on the effects of school vouchers on student achievement. Our research finds 15 U.S.-based studies using lottery-based or quasi-experimental methods to evaluate data from voucher programs in Cleveland, Ohio; the District of Columbia; Indiana; Louisiana; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; North Carolina; and Ohio to examine their effects on student achievement. Table 1 summarizes the estimated effects of these voucher programs on student reading/English language arts and math test scores.

Table 1: Effect of voucher programs on reading and math test scores

Source: Erickson, et al. (2021)

Reading statistical results indicate mixed, but slightly positive, results from voucher programs. Six studies report that vouchers have a positive effect on reading test scores, three find a negative effect, and the rest are inconclusive. Statewide studies are more likely to find a negative effect of vouchers on reading scores (1 positive, 3 negative, 2 inconclusive), while city-focused studies are more likely to find a positive effect (5 positive, no negative, 4 inconclusive).

The statistical results on the effects of vouchers on math test scores are more varied than reading results. Four report positive effects of school vouchers on math test scores, four report negative effects, and the rest are inconclusive. As with reading, statewide studies are more likely to find a negative effect of vouchers on math scores (1 positive, 4 negative, 1 inconclusive), while city-focused studies are more likely to find a positive effect (3 positive, no negative, 6 inconclusive).

There are no studies evaluating why state-level studies provide starkly different results from city-level studies. Heidi Erickson and her co-authors, writing in the Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, suggest one possible reason is the type of test used in the studies.[1] Some studies use a norm-referenced test—widely known as a standardized test—which is designed to rank and compare students with one another. These tests determine whether a particular student performs better than an average student.

In contrast, some studies use official state criterion-referenced tests. These differ from norm-referenced tests in that they compare a person’s knowledge or skills against a predetermined standard, learning goal, performance level, or other criterion. With these tests, each person’s performance is compared directly to the standard, without considering how other students perform on the test. Rather than ranking or comparing students, criterion-referenced tests often place students into categories such as “not proficient,” “proficient,” or “advanced.”

Erickson and her co-authors point out studies using standardized tests are more likely to find positive effects of voucher programs on students’ reading and math test scores. Her review also finds that studies using criterion-referenced tests are more likely to find negative effects of voucher programs on test scores. Only one of the statewide studies but all but one of the city-focused studies use norm-referenced tests to gauge the achievement effects of the programs. Thus, the differences in measured effects at the city- and the state-levels may be explained by the differences in the tests being used to evaluate the programs, rather than the programs themselves.

Erickson and her co-authors explain that state criterion-referenced tests likely are less closely aligned to the curricula used in the private schools serving voucher students. Instead, public school curricula are likely more closely aligned to the criterion-referenced tests mandated by the state. In other words, public schools are more likely than private schools to develop curriculum around the state’s criterion-referenced tests, a phenomenon widely described as “teaching to the test.”

It is also possible that the size and density of urban areas provide more—and possibly better—private school options than smaller or rural communities. Thus, it can be argued, the positive effects of vouchers diminish with the reduced private schooling options, causing statewide effects of voucher programs to be smaller than city-level effects. For example, Matthew Lee and his co-authors report that voucher students who attended private schools with larger enrollments, more school personnel per grade, a library, and located in a city are more likely to experience more positive effects on math scores from voucher programs than voucher students who attend private schools without those features.[2]

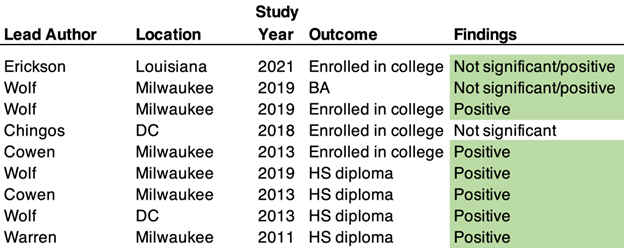

High school graduation, college enrollment, and graduation

Empirical research evaluating the effects of voucher programs on educational attainment is much more sparse than the research on reading and math test scores. Educational attainment is measured by high school graduation, college entrance, and college degree completion. The research is scarce because evaluating attainment requires following students for years—sometimes many years—after they are involved in a voucher program.

It can be argued that educational attainment is a better measure of student success than test scores. In particular, it’s not clear that a student’s score on a state criterion-referenced test is a reliable indicator of future college enrollment or graduation. Moreover, high school graduation, college enrollment, and college graduation are associated with many positive long-term life outcomes. For example, higher levels of educational attainment are associated with higher incomes, greater wealth accumulation, longer work lives, and expanded life expectancy.

Only six studies assess the impact of private school vouchers on student attainment in just three programs: (1) the Louisiana Scholarship Program, (2) the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, and (3) the District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program. Two studies consider high school graduation only, two studies consider college enrollment only, and two studies examine both. Table 2 summarizes the findings of the studies.

Table 2: Effect of voucher programs on educational attainment

Source: Erickson, et al. (2021)

Each of the four total studies evaluating the effect of voucher programs on graduation rates report statistically significant positive effects. The study of D.C.’s program reports the largest effects in which the likelihood of graduation was 21 percentage points higher for voucher students. In the Milwaukee studies, the likelihood of graduation was 2-12 percentage points higher for voucher students.

Research on the effect of voucher programs on college enrollment and graduation are more mixed. The two Milwaukee studies both find that students in the voucher program are more likely to enter four-year colleges than comparable public school students. Research on Louisiana’s program reports no significant effect of the program on students who entered the program in grades 7 or 8, but an eight percentage point increase in college enrollment for those who entered the program in grades 9 through 12. The D.C. study does not find a statistically significant effect of the program on college enrollment.

Conclusion

Voucher and ESA programs have the potential to improve participants’ academic achievement and educational attainment by providing families with the resources they need to send their children to the schools best suited to their students’ needs.

City-level evidence from voucher programs indicates that voucher participants, on average, experience higher test scores in reading and math than students who do not participate in the voucher program.

Empirical research on educational attainment—high school graduation, college admissions, and college completions—provides stronger evidence that voucher program participants experience superior outcomes relative to those who do not participate in the voucher program.

In conclusion, evidence generally indicates school voucher programs are associated with improved academic achievement and educational attainment. But, perhaps more importantly, they provide families with more options for their children’s education and can improve educational opportunities for those who otherwise would not have had the resources to choose alternatives to their local public schools.

Sources cited

Abdulkadiroğlu, A., Pathak, P. A., & Walters, C. R. (2018). Free to choose: Can school choice reduce student achievement? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 175–206.

Anderson, K., & Wolf, P. W. (2017). Evaluating school vouchers: Evidence from a within-study comparison. EDRE Working Paper No. 2017-10, Social Science Research Network, Fayetteville, AR. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/edrepub/10/.

Chingos, M. M. (2018). The Effect of the D.C. school voucher program on college enrollment. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/96686/the_effect_of_the_dc_school_voucher_program_on_college_enrollment_3.pdf.

Cowen, J. M., Fleming, D. J., Witte, J. F., Wolf, P. J., & Kisida, B. (2013). School vouchers and student attainment: Evidence from a state-mandated study of Milwaukee’s parental choice program. Policy Studies Journal, 41(1), 147–168.

Egalite, A. J., Stallings, D. T., & Porter, S. R. (2020). An analysis of North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship Program on student achievement. AERA Open, 6(1), 1–15.

Erickson, Heidi H., Jonathan N. Mills & Patrick J. Wolf (2021) The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement and College Entrance, Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14:4, 861-899

Figlio, D., & Karbownik, K. (2016). Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, competition, and performance effects. Washington D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. http://edex.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/publication/pdfs/FORDHAM%20Ed%20Choice%20Evaluation%20Report_online%20edition.pdf.

Greene, J. P., Peterson, P.E., & Du, J. (1998). School choice in Milwaukee: A randomized experiment. In P. E. Peterson & B. C. Hassel (Eds.), Learning from School Choice (pp. 335–356). Brookings Institution Press.

Lee, Matthew H., Jonathan N. Mills & Patrick J. Wolf (2020) Heterogeneous Achievement Impacts across Schools in the Louisiana Scholarship Program, Journal of School Choice, 14:2, 228-253.

Metcalf, K. K., West, S. D., Legan, N. A., Paul, K. M., & Boone, W. J. (2003). Evaluation of the Cleveland scholarship and tutoring program: Summary and report 1998–2001. Indiana University. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED479162.

Mills, J. N., Wolf, P. J. (2017). The effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on student achievement after three years (Louisiana Scholarship Program Evaluation Report #7). New Orleans, Louisiana: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. http://educationresearchalliancenola.org/publications/the-effects-of-the-louisiana-scholarship-program-on-student-achievement-after-three-years.

Peterson, P., Greene, J. P., Howell, W. (1998). New findings from the Cleveland Scholarship Program: A reanalysis of data from the Indiana University School of Education Evaluation. Cambridge, MA: Program on Education Policy and Governance, Harvard University. https://wayback.archive-it.org/8983/20200122162314/https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/pepg/PDF/Papers/newclvex.pdf.

Rouse, C. E. (1998). Private school vouchers and student achievement: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(2), 553–602.

Waddington, R. J., & Berends, M. (2018). Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement effects for students in upper elementary and middle school. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(4), 783–808.

Warren, J. R. (2011). Graduation rates for choice and public school students in Milwaukee, 2003–2009. School Choice Wisconsin. https://www.heartland.org/_template-assets/documents/publications/29370.pdf.

Webber, A., Rui, N., Garrison-Mogren, R., Olsen, R. B., & Guttman, B. (2019). Evaluation of the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts three years after students applied. U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, NCEE 2019–4006.

Witte, J. F. (1998). The Milwaukee voucher experiment. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 20(4), 229–251.

Witte, J., Carlson, D. E., Cowen, J. M., Fleming, D. J., Wolf, P. J. (2012). MPCP longitudinal educational growth study: Fifth year report. MPCP Evaluation Report #29. Fayetteville, AR: School Choice Demonstration Project, University of Arkansas. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED530071. .

Wolf, P. J., Kisida, B., Gutmann, B., Puma, M., Eissa, N. O., & Rizzo, L. (2013). School vouchers and student outcomes: Experimental evidence from Washington, DC. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 246–270.

Wolf, P. J., Witte, J. F., & Kisida, B. (2019). Do voucher students attain higher levels of education? Extended evidence from the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. EdWorkingPapers. Annenberg, Brown University, Providence, RI, http://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai19-115.

[1] Heidi H. Erickson, Jonathan N. Mills & Patrick J. Wolf (2021) The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement and College Entrance, Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14:4, 861-899.

[2] Matthew H. Lee, Jonathan N. Mills & Patrick J. Wolf (2020) Heterogeneous Achievement Impacts across Schools in the Louisiana Scholarship Program, Journal of School Choice, 14:2, 228-253.

Eric Fruits, Ph.D. is Vice President of Research at Cascade Policy Institute. He is also an adjunct economics professor at Portland State University.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.